- The 9 steps a prospective parent takes to adopt a child – What are the required documents, what forms should be filled out – The types of legal adoption and foster care

- How many adoptions and foster care placements have taken place in Greece in 2020-23, and how many multiple applications are pending?

- The cases of illegal trafficking of babies in Greece, the last one being in January 2024 – How did the circuit work, the fees of the lawyer-mediator and the conviction

- The “price list” of adoptions: From 10,000 to 28,000 euros per adoption – The price of mediation

- Codename “Leto”: A lawyer with an office in Athens and Thessaloniki, a doctor and a midwife with women from Bulgaria, Georgia.

- The Law on Fostering and Adoption in Greece – What it provides, its main points and its main pillars.

- Theano Fotiou, former Minister of Labor and Social Security, speaks to Data Journalists, who in 2018 proposed a law aimed at de-institutionalizing children and streamlining related procedures in Greece.

By Vassilis Galoupis, Vangelis Triantis, Panos Katsahnias,

Governments claim to facilitate adoption and fostering, but in practice prospective parents are subjected to a long and desperate ordeal. In 2013, the average time to adopt a child from a state institution was 5 years. Today, a couple who has decided to adopt a child can wait from 3-3.5 to 15 years before welcoming the child into their home.

In addition to the understaffing of the relevant services, extensive bureaucracy, labyrinthine legislation and long delays, there is now a shortage of children available for adoption. Combined with all of these factors, the desire of couples to have a child creates an increasingly fertile ground for illegal networks to operate in the shadows of the official adoption system, making huge profits through dubious practices.

Data Journalists’ research focuses on all steps of the adoption and fostering process in Greece, the relevant legislation and its changes, as well as cases of illegal trafficking of infants.

According to the latest official data, in the second quarter of 2023, 1,351 children were registered in the National Register of Minors, living in 98 child protection units in the country.

An “Individual Family Rehabilitation Plan” (IFRP) is prepared for each minor, which includes a reasoned proposal for his/her rehabilitation based on his/her individual needs and best interests. IFRPs are divided into adoption/foster care, kinship adoption/foster care, return to the natural family and those who are not rehabilitated in a family.

Of the 1,351 children, only 149 are up for adoption and another 571 are in foster care.

Of the 149 to be adopted, according to official figures, 37 are between the ages of 15 and 18 and 58 are between the ages of 12 and 15. The number of children in foster care at these ages is 132 and 190, respectively. At the ages of 0-2 and 2-6 there are a total of 8 for adoption and 42 for fostering.

Between 1/7/2020 and 2/7/2023, 662 adoptions of minors and 574 foster care placements were completed.

However, as of 2/7/2023, there were 3,089 applications pending or in progress in the system (2,639 for adoption and 445 for foster care).

According to the data in the system of the General Secretariat of Population and Housing Policy, in January 2024 there were 1,265 children in institutions across the country (compared to 1,351 in July 2023). Of these, 110 are available for adoption, while another 110 are in what the authorities call a “matching process,” meaning the introduction between the child and prospective parents.

The children are placed in public, private and church institutions. In particular, of the 512 children in public institutions, only 47 are available for adoption, while in private and church institutions there are 753 children, of whom only 63 are available for adoption. The remaining children are in the legal process of being returned to their biological families for fostering or are disabled, for which different procedures are followed.

Official figures for the second quarter of 2023

Since 2019, the official information system anynet.gr has been operational, implementing Law 4538/2018 “on fostering and adoption” and guiding prospective parents with the Taxisnet code.

The three types of legal adoption and foster care

Adoption is the legal act by which a child acquires the same legal relationship with his or her adoptive family as any child has with his or her biological family. When a child is adopted, all legal and physical ties to his or her biological family are severed.

Foster care occurs when a child cannot live with his/her biological family for a short or long period of time and a foster family is sought to ensure the child’s smooth psychosocial development in a family environment and to avoid institutional care. If suitable relatives are available, it is preferable that they become foster parents.

The three types of legal adoption are:

- Private Adoption: A person or family adopts another person’s child, whether the child belongs to a relative or a stranger.

- Institutional (public) adoption: A person or family adopts a child from an institution.

- Intercountry Adoption: A person or family adopts a child from another country under the Hague Convention.

The basic requirements for adoption, as far as the adoptive parents are concerned, are age (at least one of the two prospective adoptive parents must be over 30 and under 60). In addition, the adoptive parent must be at least 18 years older than the adoptee, but not more than 50 years older), a clean criminal record, financial situation, good mental, intellectual and physical health and, in particular, no chronic communicable diseases.

In the case of private adoption, the final consent of the biological parents must be given three months after the birth of the child. In the case of a private adoption, the prospective adoptive parents are required to draw up a notarial deed indicating the consent of the biological mother to the temporary placement of her child.

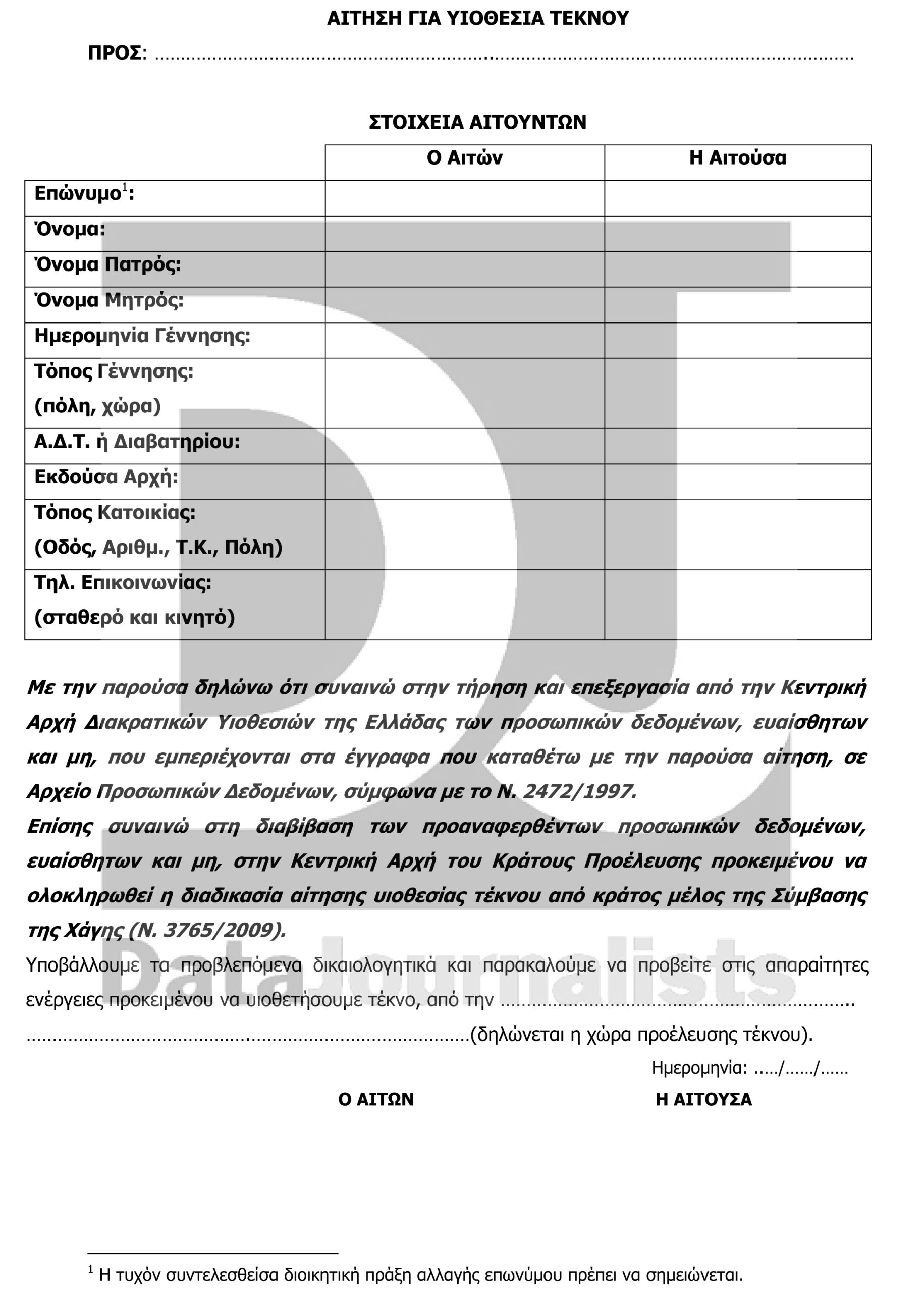

The official adoption application and supporting documents form, as currently available on the Ministry of Health’s platform (pdf )

The 9 steps of an adoption and the supporting documents

First of all, the person concerned must submit an official application for adoption, accompanied by several documents (photocopy of identity card, medical certificates from a public hospital and a sworn statement that he/she is not a fugitive, his/her address, who he/she lives with, tax statement for the previous year, certificate of income or pension, etc.). In total, the procedure consists of 9 steps:

- Application of interest on the online platform www.anynet.gr, after the person concerned has been informed by the social services about the adoption institution. The application is submitted either by computer using the Taxisnet access codes, or in person at one of the competent social services in the place of residence (Regional Social Welfare Centers, Regions, Regional Units).

- If the applicant is married, a letter of consent from the spouse is also required.

- Completion of the fields of the application form that are not pre-populated and submission of supporting documents. Those that are not available online must be scanned prior to submission.

- Until the final submission of the application, it is stored temporarily, with the possibility of modifying or deleting data and adding supporting documents. From the moment of final submission, the person concerned should contact the competent social service for any change that may occur (e.g. change of residence). When the application is finally submitted, he/she will receive a registration number that will allow him/her to follow the progress of the application at any time.

- This is followed by a review of the supporting documents. A qualified social worker is then hired to conduct a social investigation of the family environment to assess living conditions, motivation for adoption, and the specific possibilities and wishes of the individual. All parties involved have a strict obligation to respect the confidentiality of personal data. According to the new law on the promotion of fostering and adoption institutions, the social investigation is completed within six months of the assignment to a social worker.

- Once the social screening is completed with a positive result, the person is invited to attend a short training program and a number of important details are clarified. The training takes place in one of the major cities of the country, taking into account the candidate’s place of residence. There are cases where the social investigation does not have a positive result. In this case, the candidate may reapply after three years, after being informed of the reasons for the rejection.

- Upon completion of the training, the interested party is registered in the National Registry of Prospective Adoptive Parents. As soon as a child whose needs, as determined by various specific characteristics such as age, health status, etc., match the capabilities and desires of the prospective parent, as recorded during the social investigation, the prospective parent is contacted by the relevant social service and informed accordingly. At this stage, the information system ensures equity: if the characteristics of the child and the family match, the order of priority determined by the registration in the National Registry is not bypassed.

- This is followed by a period of familiarization with the child. This always begins in the child’s natural environment, under the supervision of trusted persons who know the child and are entrusted with it, and who gradually assess whether this particular adoption is in the child’s best interest. After a positive recommendation from a multidisciplinary committee, the final adoption decision is made and the legal process is initiated for the adoption to take place. In most cases, the child is placed with the adoptive family before the court decision is made, if common experience suggests that this will be beneficial.

- The child now has a new family environment. The relevant social services stay with the foster family for three years to monitor the child’s development, to support the family, to help with difficulties, to give advice and, if necessary, to prevent risks.

Infant Trafficking

At the same time, dozens of cases involving the illegal trafficking of infants have been brought before the courts. The most recent was just a few weeks ago.

It was mid-January 2024 when the Thessaloniki Court of Appeals sentenced a lawyer to four years in prison for facilitating illegal adoptions, with a focus on northern Greece.

Specifically, the lawyer was found guilty of the crime of “repeatedly mediating in illegal adoptions for the purpose of unfair joint benefit, for profit, and professionally”.

The court recognized two mitigating circumstances, while his sentence was suspended on the condition that he donate the sum of 3,000 euros to the Smile of the Child. The same sentence had been imposed by the court of first instance.

How the adoption ring worked

This case involved five cases of illegal adoptions. Four of them in 2016 and the other, two years earlier, in 2014.

The ring worked as follows. Women of Bulgarian origin were persuaded to come to Greece to give birth in certain clinics. These were women with serious financial problems, many of them from Roma families. With their consent, they sold the babies they gave birth to, which were then offered for adoption by the ring to interested families.

According to the case file, the convicted lawyer’s net fees exceeded 32,000 euros. He denied the charges in his apology. He claimed that the fees were for clinics, notaries, etc. The biological mothers were also initially charged.

In his apology, the lawyer denied the accusation, as well as the fact that the money ended up with him, claiming that it was fees for clinics, notaries, etc.

Code name “Leto”

This is not the only case of a ring of illegal adoptions that has occupied the Greek Justice in recent years. In September 2019 another case of illegal adoptions shook the society of Thessaloniki.

After eight months of close surveillance, police officers from the Hellenic Police’s Sub-Directorate for Combating Organized Crime and Human Trafficking managed to dismantle a circuit that was active in both the egg trade and the buying and selling of babies. The file that was created included dozens of people involved and thousands of conversations between them. The Hellenic Police operation lasted several months and was codenamed “Leto”.

A lawyer with offices in Athens and Thessaloniki, a doctor and a midwife are the protagonists in the sale and purchase of babies. According to the police investigation, these three people targeted childless couples who wanted to have a child. They then instructed two women from Georgia to find pregnant women willing to give up their children for adoption immediately after birth. The women did indeed find such women. The vast majority were from Bulgaria.

The ring paid for pregnant women to travel to and from Bulgaria. The money was used to pay for their hospitalization in private or public clinics and their stay in the country. According to information, the women usually arrived in Greece in the fifth or sixth month of pregnancy and stayed in the country for up to two months after giving birth.

From €10,000 to €28,000 per adoption

In some cases, part of the cost was borne by the “prospective” foster families. The “price list” for adoptions ranged from 10,000 to 28,000 euros. Of these:

1,500 to 3,000 euros for the hospitalization and delivery of the pregnant woman in Greece.

4,000 to 6,000 euros for the birth mother, depending on the sex of the child to be adopted.

The lawyer’s fees ranged from 2,500 to 3,000 euros.

All of this was done when the foster family had been previously identified and discussions had taken place. If the foster family had not been identified by the leaders or another member of the organization, the mediators were responsible for finding a foster family. The cost of mediation was reported to be 5,000 Euros.

The payment to birth mothers was not a lump sum, but was paid in three installments. The staggered payment was not a haphazard choice, but was intended to ensure that the birth mother was present at every stage of the adoption process so that it was legal.

Another case in 2022 in Thessaloniki

In June 2022, another case of illegal buying and selling of infants came to light in Thessaloniki. Police officers arrested five people for illegal infant adoption. They were the biological father and mother of the infant, a couple who were supposed to buy the child, and a lawyer who allegedly played an intermediary role.

As in other cases, the biological parents were Roma of Bulgarian origin. The arrested persons claimed that this was a legal case of infant adoption. According to the information available, the biological parents had three other children and were unable to support the child due to financial problems.

According to the Hellenic Police, by June 17, 2022, the prospective parents had paid 1,435 euros, an amount initially characterized as a deposit. The woman actually came to Thessaloniki, where she gave birth in a clinic. Before the birth, the prospective parents paid an additional €2,400 for medical expenses.

The suspects were eventually released. The biological parents denied that they wanted to sell their child, while the prospective parents claimed that they believed it was a legal adoption.

Identical Mode of Operation

From the dozens, if not hundreds, of case files that have accumulated over time, it appears that the mode of operation of the networks involved in illegal adoptions and baby trafficking is identical.

Bulgarian criminal organizations, taking advantage of financial hardship, encourage young Bulgarian women in advanced pregnancy in Greece to give birth in Greek hospitals or approach couples who have just had a child.

The women come mainly from villages on the Bulgarian border, where poverty and misery lead them to sell their children for a few thousand euros. In some cases, the rings persuade their young compatriots to become pregnant for the sole purpose of selling their children to childless couples in Greece.

The young Bulgarian women are brought to our country with the help of members of the rings. They stay for some time in apartments rented by the rings and then give birth in a hospital.

As is clear from the cases brought before the Court, Greek pediatricians, obstetricians, notaries and various mediators are involved in the process to make it legal. According to the same sources, even today a couple has to pay around 20,000 euros to have a baby, while for twins the amount is as high as 35,000 euros. This does not include the cost of food for the pregnant woman in Bulgaria and the cost of delivery in our country.

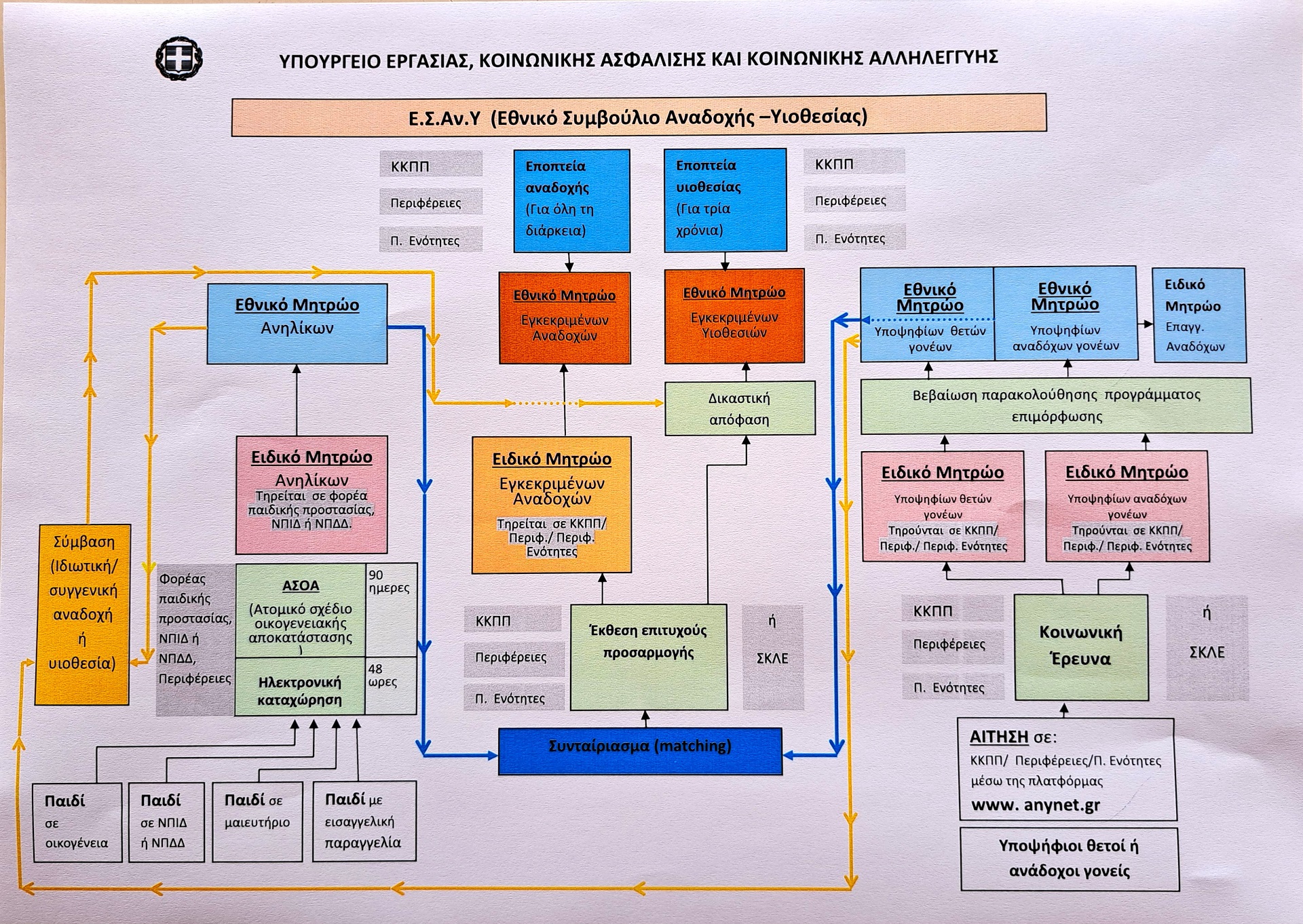

The outline of how the adoption and foster care system works. The left pillar concerns the children, the right pillar concerns the parents and the middle pillar is the combination of the two pillars under the auspices of the state.

The 5 keys to the law on foster care – adoption in Greece

The Member of Parliament of the New Left (elected with SYRIZA – Progressive Alliance), Theano Fotiou, as Deputy Minister of Labor, Social Security and Social Solidarity in the SYRIZA-ANEL government of 2018, proposed the law on fostering and adoption, aiming at the deinstitutionalization of children in child protection institutions, as well as the rationalization of the relevant procedures in Greece.

The draft law: “Measures for the promotion of the institutions of fostering and adoption and other provisions” was voted for by SYRIZA, ANEL, New Democracy, Democratic Rally and Potami in the plenary session of the Greek parliament in 2018, with KKE declaring itself “present”, while the Centrists’ Union and Golden Dawn voted against it.

A roll-call vote was taken on Article 8, which allows same-sex couples in a civil partnership to become adoptive parents. Of the 264 MPs who voted, 161 voted for the article and 103 voted against. At the time, New Democracy had extensively debated the provisions of this particular article to such an extent that very little was said during the public discussion about the radical changes that the new law as a whole brought to the adoption and fostering procedures.

According to Theano Fotiou, who spoke to Data Journalists on the issue, she made it clear from the outset that there are objectively few children available for adoption in Greece, especially infants and toddlers. Older children are difficult to adopt, which is why they remain in institutions. As for foster care, which is the greatest need, the supply is small.

According to the former minister, the main problems that Law 4538/2018 sought to address were:

The very long waiting period of up to 8-10 years for prospective adoptive or foster parents, during which the state did not provide them with any information on the progress of the whole procedure (adoption is validated by a court, fostering is not).

The way the whole procedure was handled, where the prospective parent – foster or adoptive (mostly foster) – went to an institution (mainly “Mitera”) and tried to find a child, creating a de facto accumulation of prospective parents there. Therefore, Law 4538/2018 sought to reduce the time of the whole procedure and provide transparency, as prospective parents are now directed to wherever there are children in Greece, and not only to specific institutions: both public law legal entities (13 structures nationwide) and private law legal entities (e.g. “Smile of the Child”, “Ark of the World”). As of April 18, 2019, all adoption and foster care applications will be registered in the Adoption and Foster Care Information System (https://www.anynet.gr/).

Dealing with all the parallel circuits that operated mainly through public maternity hospitals, exploiting infants who were brought in, mostly under false names, born in them, and then abandoned. The children remained there for a short time and then either went to an institution or “disappeared”. The creation of the Special Register of Juveniles is now a key element, so that all children living in institutions can be registered with all their data and history (number per unit, age, length of stay in the institution, reasons for placement, personal details of themselves and their families).

Supervision of procedures in cases of private fostering and adoption. That is, when a family decides on its own to give up its child for adoption, without certifying the suitability of the foster or adoptive parents and without assessing the child’s condition, especially psychological.

To make the whole process transparent. This has been achieved by requiring that the necessary stages be carried out digitally, thus avoiding “manual” external intervention, with personal meetings and interviews and the opinions of specialists being provided only for the stages required by the procedure. In addition, both the parties directly involved and the National Adoption and Fostering Council, whose establishment was provided for in the law, can monitor the entire process of adoption or fostering (including those involving professional fostering of children with disabilities).

Ms. Fotiou shed light on another important parameter of the law: “Adoption and fostering are acts of altruism and not acts that should be hidden. That’s why the procedure foreseen now allows an adopted child – because in fostering, not only is it known, but contact with the parents is provided for – when he or she comes of age, and of course if he or she wants to, to easily search for his or her biological parents, since his or her adoption history is obligatory recorded.

Finally, she mentioned the importance of the changes brought about by Law 4538/2018, which was evident from the communicative approach when, after the parliamentary elections of July 7, 2019, the New Democracy government not only did not repeal it, but “inaugurated” it twice more. Kyriakos Mitsotakis himself did so at the end of 2019 and then again in March of the following year. However, according to Ms. Fotiou, there are also side effects of the law: for example, the raising of the age limit for parents in foster care from 60 to 75 (the limit for adoption remains at 60, as does the limit of 15 years from the age of the child).

It should be noted that there are very few cases of orphans in institutions. That is why we do not call them “orphanages”. Because in the majority of cases when children lose their parents, they are taken care of by their relatives. Thus, the institutions are mainly places where children are placed by order of a prosecutor because of an abusive environment.

Discussion about this post